East African Sails

Impressions that evoke the times of Sindbad.

After all, the Omanis and other Arabs sailed down to the East

African coast since the Middle Ages. Their main trade goods were

slaves and mangrove poles. Today the mangrove poles remain, but

consumer goods and staple food stuffs have replaced the slaves.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dar-es-Salaam

roadstead |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Setting sail and getting under way, Stone Town harbour, Zanzibar | Dar-es-Salaam roadstead | |||||||

Different Types of Boats

The classification of boats around the East

African coasts meets with many difficulties. While we modern

Europeans tend to base our taxonomy of boats on

phenomenological, that is constructional criteria, the Africans

use functional criteria (WINKLER, 2009). As a

result, vastly different boats can be given one and the same

denomination, resulting in confusion and a lack of traceability

in history. In the following, a range of boats encountered

during a visit in September 2012 will be presented and compared

with what was found in the literature.

The Mtepe

The Mtepe, actually a 'living fossil', was a double-ended boat with a sewn hull, propelled by a single square sail made from matting. It disappeared only in the 1930s (GILBERT, 1998).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

Mtepe-replica in the House

of Wonders, Stone

Town, Zanzibar. |

|||||||||

Dugouts

Dugouts are one of the primordial forms of boats and they are still in use along the coast of East Africa. There are several types of dugouts in use today: dugouts fashioned from a single tree (Mtondoo, Callophyllum inophyllum) , dugouts with extensions (or worn parts replaced) and extended dugouts with double outriggers. The simple dugouts are being used for angling in sheltered waters as well as tenders for larger dhows.

The lateral profile of individual boats can differ considerably, presumably depending on the shape and quality of the trees available. There seems to be also a transition between the simple (Hori) and the extended dugout. As the former becomes worn out, bad pieces are cut out and replaced by planks, making it finally difficult to decide into which group the boat belongs now. Many of the double-outrigger boats (Ngalawa) have a shovel-shaped bow piece inserted, but by no means all of them. Most boats have the wale reinforced by an out-wale that runs along the whole length and is nailed down, rather than dowelled, as the extension pieces obviously are. The simple dugouts fashioned from a single tree do not have a re-inforced wale. The trees, or even the pre-prepared dugouts are imported from India, as there are no suitable trees available anymore in the coastal region of East Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dugout used for angling | Dugout

being hauled ashore |

Dugout used as a

tender for a dhow |

Dugouts without plank extensions | Extended dugouts | ||||||

| Dar-es-Salaam |

||||||||||

The floats of the outriggers are thin boards

with pointed ends and thus do not provide much static buoyancy

compared to the outriggers of Asian or Pacific boats. I did not

see any boat sailing in stronger winds, but would suspect that

some of the buoyancy is dynamic, rather than static. According

to WINKLER (2009) the way, how the outriggers are

attached to the hull and the constructional details of the

outriggers vary between the mainland and Zanzibar. However,

comparing the pictures of boats from the harbour of

Dar-es-Salaam and Nungwi, one notes that in both cases the main

traverse is lashed down to the inside of the hull. There are,

however, constructional differences in the way the float is

attached to the main traverse.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Derelic(?) extended dugouts without outriggers fitted | |||||||||

| Nungwi, Northern Zanzibar | |||||||||

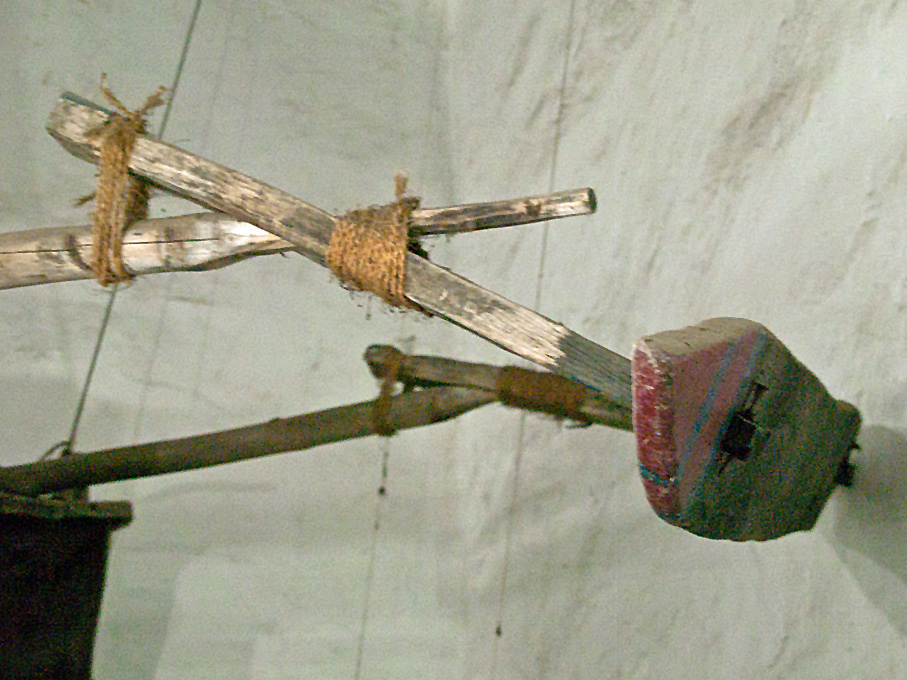

The double-outrigger boats are fitted with a

triangular (lateen) or a settee sail with a very short forefoot.

The distinction between the two types is sometimes not very

sharp as the forefoot can almost disappear in the rather rough

fashioned sails. The mast is stepped into a mast spur and a

thwart that is lashed down onto the bulwark. All spars are made

from mangrove poles. The spar for the settee on larger boats is

made from two or three poles, while smaller boat get away with a

single piece.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Extended dugouts with two outriggers (Ngalawa) | Extended

dugouts with two outriggers |

Extended dugouts with two outriggers (Ngalawa) | ||||||||

| Dar-es-Salaam |

House

of Wonders, Stone

Town, Zanzibar

|

Nungwi, Northern Zanzibar | ||||||||

There are neither forestays (which would get

into the way of the spar for the settee sail) nor shrouds, only

a flying backstay. The halliard for the spar serves as an

additional backstay. The rig does not make use of any blocks and

the halliard for the spar is reefed through a hole in the mast.

All sheets etc. are simple pieces of rope. Halliard, backstay

and sheets are belayed on whatever appears to be a convenient

point, no clamps or the likes are foreseen for this purpose.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Constructional details of extended dugouts with two outriggers (Ngalawa) |

Extended dugouts with two

outriggers under sail

|

||||||||||

| Nungwi, Northern Zanzibar | |||||||||||

The use of outboard engines (mostly of

Japanese origin) is quite ubiquitous and some of the dugouts

have short horizontal pieces of wood bolted to their stern for

suspending there such engines. Engines seem to be more common on

larger, plank-built boats. The main means of propulsion still

are sail and simple paddles.

It appears that the boats in Nungwi are not normally painted, while some of the dugouts in Dar-es-Salaam have their lower hulls painted red like that of the larger dhows.

Unlike for plank-built dhows (see below) I did not see any place where the dugouts were made. Large trees are rare in East Africa and on Zanzibar so it is probable that suitable logs are imported from Asia, across the Indian ocean. It is mentioned in the literature that dhows employed in the trade to India often took a half-finished dugout as deckload to be sold in areas where no large trees are available.

Plank-built DhowsIt appears that the boats in Nungwi are not normally painted, while some of the dugouts in Dar-es-Salaam have their lower hulls painted red like that of the larger dhows.

Unlike for plank-built dhows (see below) I did not see any place where the dugouts were made. Large trees are rare in East Africa and on Zanzibar so it is probable that suitable logs are imported from Asia, across the Indian ocean. It is mentioned in the literature that dhows employed in the trade to India often took a half-finished dugout as deckload to be sold in areas where no large trees are available.

The term dhow may refer to boats and ships of

quite different size and shape. Originally, dhows seem to have

been double-ended, but at least since the 16th century European,

namely Portuguese, shipbuilding fashions appear to have

influenced the shape and design of the larger, mainly Omani,

dhows. These influences also spread along the Arab trade routes

down to East Africa. Today there are double-ended dhows, as well

as those that have a transom stern. The majority seem to have a

transom, as this facilitates the attachment of one or two

outboard engines. The local trading dhows use the outboard

engine mainly for maneuvring, while the main means of propulsion

still is the sail. Fishing boats also use their engine when

actually engaged in fishing with the seine net.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fishing dhows at Nugwi, Zanzibar | |||||

A large number of smaller dhows with a

clipper-like bow are employed in the seine-net fisheries.

A GRP

fishing boat probably of FAO-design, sunk in

the harbour of Stone Town on Zanzibar indicates that this

material is much less adapted to the local socio-economic

circumstances than the the traditional wooden dhow.